I first remember that feeling when I met the opening pages of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, a book to which I feel an uncanny and unwavering devotion.

And most recently, I remember that feeling when I met the opening pages of Colum McCann’s tour de force Transatlantic.

What agents see that you don’t

Why do first pages matter? And for that matter, why do literary agents ask you to only send 30 pages or the first chapter when they’re deciding whether they will take on your book?

How can they know?

The answer: When it’s right, it’s right. And the first pages will reveal that.

They will also expose all the flaws. They will throw a spotlight on anything that it is off and not functioning well. They will reveal what you yourself, even as the author, are fuzzy about. They will reveal all the places where you haven’t yet made clear decisions as author.

In writing, this is called the point of authority or authorial presence. In the first pages, as much as the reader is wanting to be transported into the story, the reader also is seeking reassurances that he or she is in good hands. You’ve got this.

Once, listening to an agent panel at the annual Association for Writers and Writing Programs conference, one agent said the big mistake of most first pages he sees is that the manuscripts are too “young.” That was his kind way of saying that authors send their first pages in too early, when they are still in the early draft stage, when the vision for the book has not yet snapped into high-definition.

On the Writer’s Digest agent blog, Chuck Sambuchino tells about an experiment at a writing festival where an actress randomly picked opening pages to read aloud to an agent panel. Agents were instructed to raise their hands when they would stop reading. She was only reading 250 words, or one page of double-spaced 12-point Times Roman. That’s a realistic picture of how much time you have to win over an agent—or a reader! Less than 25 percent of the pages made it to the end of the passage.

Here are the reasons the panelists gave:

- It’s generic. We’ve seen it before. About ten thousand times.

- It’s slow. It doesn’t seem like it’s off and running.

- The author is trying too hard. The prose is flowery, and the imagery is forced.

- It’s full of cliches.

- It’s hard to know what the focus is, what the book is most concerned with.

- It feels contrived.

And toward that end, I’ll offer you some test questions that will help you drill down further and get past some of these pitfalls with a “young” manuscript:

- Is your character gripping? Complex characters are fascinating.

- Does your character have an external struggle and an internal struggle? The story is never just about what it says it’s about. Harry Potter isn’t just about a boy who goes to wizard school; it’s about a boy becoming a hero.

- Is the plot off and running? Does something seem not quite right, even from the first line?

- Did you start in the right place? Establishing the point of narration is one of the most important decisions the author makes. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, this choice was crucial.

- Is something meaningful at stake?

- What forces oppose the protagonist?

- Is your story set in a real place and real time with a real person? Many first pages meander or seem unfocused because they suffer from “white room syndrome,” one deeply thoughtful person alone in a white room, thinking big thoughts.

- Are your pages powered by sentences that sparkle?

- Is something not what it seems? Is this a world about to be broken?

A masterful opening

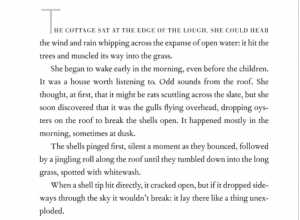

Here is a glimpse into Colum McCann’s first pages, which are a prologue that sets up the first section, the first-ever transatlantic flight in June 1919 of Alcock and Brown. Notice that the prologue is set in 2012. This already signals the span of this novel will be oceanic in geography and time.

In this opening, you get the sense that something is arriving, and it is imminent. What is it? This isn’t just description of a setting. It’s dynamic. In fact, the setting seems to be alive, personified. The wind and rain muscle their way into the grass. The oyster shells lay like “a thing unexploded.” This feels potent.

That’s just a taste. In The Story Catalyst I: Writing First Pages That Sparkle, my online class, we dive deeper into these questions. I’ll help you diagnose what’s missing and identify the ingredients that need to be refined in your first pages. Find out more here!

NEXT TIME | When prologues work, when they don’t